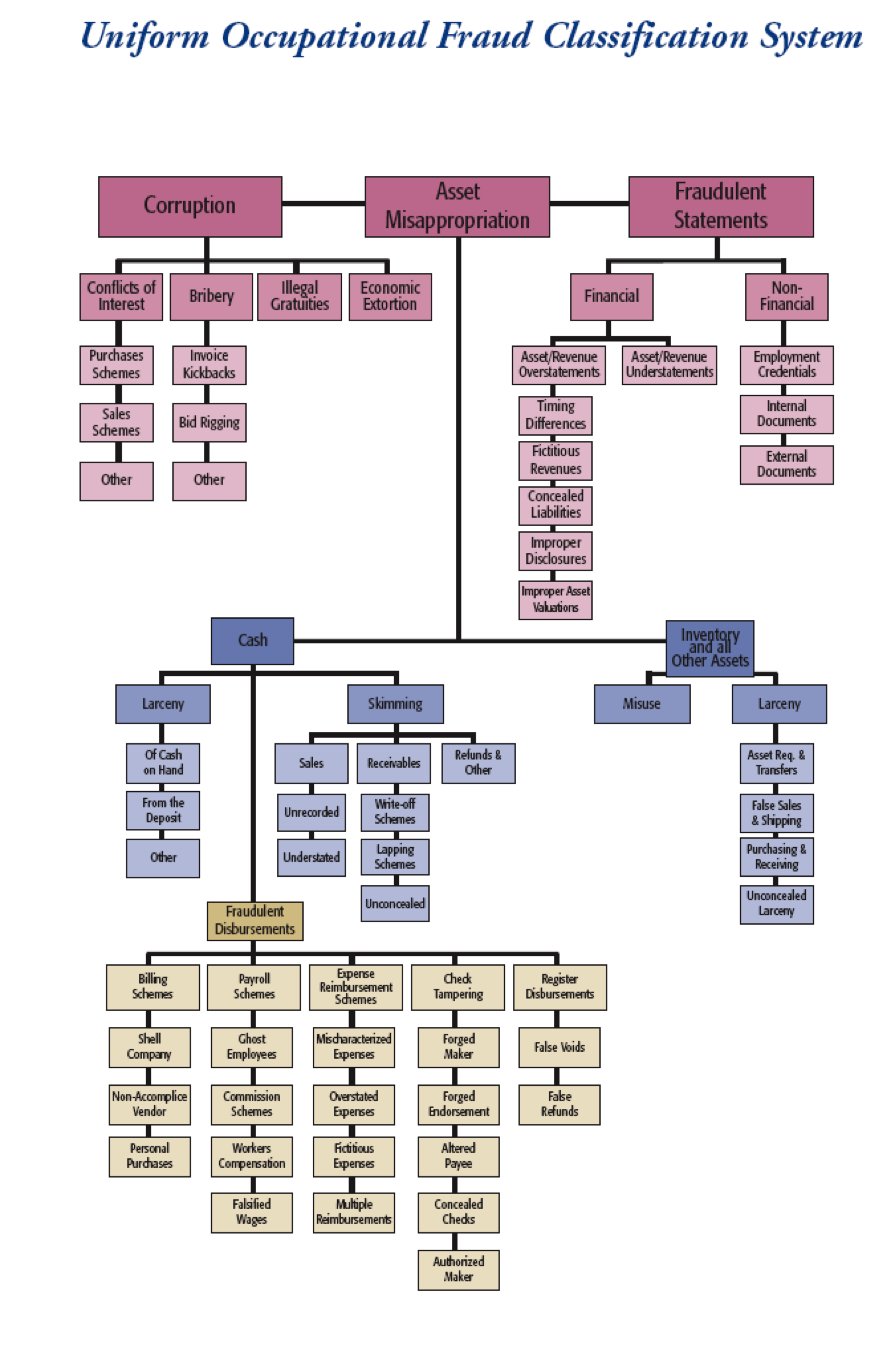

In our last chapter, we discussed the fraud tree – a taxonomy of fraud created by the Certified Fraud Examiners. Now we are going to look at another model created by the Certified Fraud Examiners which is also mentioned in the GAO’s Green Book – the fraud triangle.

The GAO’s Green Book calls the three components of the fraud triangle ‘fraud risk factors’:

8.04 Management considers fraud risk factors. Fraud risk factors do not necessarily indicate that fraud exists but are often present when fraud occurs. Fraud risk factors include the following:

- Incentive/pressure – Management or other personnel have an incentive or are under pressure, which provides a motive to commit fraud.

- Opportunity – Circumstances exist, such as the absence of controls, ineffective controls, or the ability of management to override controls, that provide an opportunity to commit fraud.

- Attitude/rationalization – Individuals involved are able to rationalize committing fraud. Some individuals possess an attitude, character, or ethical values that allow them to knowingly and intentionally commit a dishonest act.

I ‘d seen that triangle dozens of times, but never took it seriously until…

The audit profession underwent a significant transformation in the 90’s. Auditors acquiesced to customer expectations and agreed to perform some due diligence procedures regarding fraud. So fraud became the training and discussion topic of the moment, and I must have attended over a dozen seminars and read countless articles and books that contained the fraud triangle. I saw it so often, I started to wonder if it is was any good… kind of like that annoying pop song that you hear 10,000 times each summer. (I swear if I hear “Renegades” one more time, I’m gonna…! Jeep even uses it to sell Renegades on television commercials! I can’t escape that song…ARGH. )

The audit profession underwent a significant transformation in the 90’s. Auditors acquiesced to customer expectations and agreed to perform some due diligence procedures regarding fraud. So fraud became the training and discussion topic of the moment, and I must have attended over a dozen seminars and read countless articles and books that contained the fraud triangle. I saw it so often, I started to wonder if it is was any good… kind of like that annoying pop song that you hear 10,000 times each summer. (I swear if I hear “Renegades” one more time, I’m gonna…! Jeep even uses it to sell Renegades on television commercials! I can’t escape that song…ARGH. )

But then I sat down to write a book an auditor’s responsibility to detect fraud. I used the fraud triangle to frame a story about a fraud committed by a close family friend against my uncle and his business. See the story here in this blog post: https://yellowbook.ideamakr.com/my-

As I wrote that story, I got a sinking feeling that I couldn’t shake. I suspected that one of my client’s was suffering fraud, too. Of course, I lacked confidence in my feeling because, once I started writing that book on fraud, I suspected everyone of fraud, even the guy selling pizza slices at the mall! But when it came to this client, a boutique hotel owner (we’ll call her Jesse), I was actually right.

Jesse, Eowyn and $30,000 in Credit Card Charges

Jesse is very creative and constantly creating super cool venues and experiences for the hip Austin community. She designed her hotel in Austin with artists and musicians in mind. Bob Dylan was known to hang out in Jesse’s hotel and as of late, she and her girlfriend have been hanging out with Robert Plant – you know, the lead singer of Led Zepplin. Soooo cool.

Jesse hired me (unhip and uncool CPA me) to teach her artist-and- musician-employees-turned-

Eowyn was so hard to work with that I eventually gave up working for Jesse. Another reason I stopped working for Jesse is that she was hard to get a hold of. Jesse was super busy creating other ventures and enjoying her rich social life, and she had left cranky Eowyn in charge.

Eowyn wouldn’t show up for meetings, refused to get me the information I requested, and was aggressive and ornery. When I asked questions, she was evasive and promised that she’d do some research and get back with me. She didn’t get back to me. Several times she set a meeting with me that she didn’t bother to attend.

So once, I surprised her and showed up at her office without an appointment. But instead of giving me what I wanted, she wasted a whole hour telling me all about her sordid personal life. She told me all about her multiple children and multiple lovers and unemployed ex’s which all sounded like they were living with her and her kids. And although I knew that she was making about $15 an hour and was in her late 20’s, she was sending her two kids to one of the most expensive schools in town.

Eowyn was also very cozy with several other female staff members who were also vaguely unhappy. Eowyn and her posse were not close to Jesse and her top managers and often made snarky comments to put down the managers. Eowyn and her posse were quick to support each other and shift blame to others for any problem they themselves caused.

And although Jesse offered several times, Eowyn turned down help with her recordkeeping. Eowyn demurred and said she was fine, but looking back, it was obvious she wanted to control the records herself.

How could I have missed it earlier? Eowyn had every facet of the triangle covered – opportunity, pressure, and justification. Eowyn had the opportunity to steal because Jesse wasn’t watching very closely. She was too busy running her hip and cool empire. Eowyn definitely had pressure, I mean, supporting a crew of underemployed hipsters and children can’t be cheap! And although I couldn’t get in Eowyn’s head to figure out how she justified stealing, she might have said something to herself like, “I’m underpaid and Jesse and these managers don’t appreciate me!”

Once I recognized what was going on, I wrote to Jesse (because I could never get her on the phone) and told her to sit down. I wrote that I suspected Eowyn was stealing from her. She was amazed at my insight because she had just hired an experienced accountant with a background with Marriot hotels who had informed her that Eowyn had taken over $30,000 from Jesse using the hotel’s credit card.

I felt good that I had finally seen it and that I had finally used that suspiciously ubiquitous fraud triangle for a real life situation, but I also felt like a jerk that I had not recognized what Eowyn was up to earlier. I still feel like a jerk because if I’d ‘clicked’ earlier, I could have saved Jesse $30K. There Eowyn sat right in front of me, time after time displaying all of the markers of a fraudster – opportunity, pressure, and lots and lots of attitude, and I didn’t see it!

Other clues indicating fraud

So please, take if from me, that silly triangle works. As does this list of fraud indicators from the State Auditor and Inspector of Oklahoma https://www.sai.ok.gov/Search%

Common Personality Traits of Fraudsters

- Wheeler/Dealer

- Domineering and Controlling

- Doesn’t like people reviewing their work

- Strong desire for personal gain

- Have a “beat the system” attitude

- Live beyond their means

- Close relationship with customers or vendors

- Unable to relax

- Often have a “too good to be true” work performance

- Don’t take leave time or only in small amounts

- Often work excessive/unnecessary overtime

- Outwardly appears to be very trustworthy

- Often display some sort of drastic change in personality or behavior

Common Sources of Pressure

- Medical problems – especially for a loved one

- Unreasonable performance goals

- Spouse loses a job

- Divorce

- Starting a new business or an existing business is struggling

- Criminal conviction

- Civil lawsuit

- Purchase of a new home, second home or remodel

- Need to maintain a certain lifestyle – Individual or spouse either likes expensive things or feels pressure to “one up” others regarding material possessions.

- Excessive gambling

- Drug or alcohol addiction

Changes in Behavior

- Suddenly appears to be buying more material items

- Brags about new purchases

- Starts carrying large amounts of cash

- Creditors/bill collectors call or come by work

- Borrows money from coworkers

- Becomes more irritable or moody

- Becomes unreasonably upset when questioned

- Becomes territorial over their area of responsibility

- Won’t take leave or only takes leave in small increments

- Works unneeded/unnecessary overtime

- Turns down promotions

- Starts coming in early or staying late

- Professes need to redo or rewrite work to “make it neat”

- May begin mentioning family or financial problems

- Exhibits signs of drug or gambling addiction

- Exhibits signs of dissatisfaction

Eowyn embodied a good number of those indicators. Man, I should have paid more attention in those fraud classes!

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website:

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: