Enjoy this excerpt from the self-study book “Audit Requirements for Federal Grants”.

Objectives:

- Identify the significant differences between a commercial financial audit and a Single Audit

- Identify the three subjects of the Single Audit

- Identify which federal grant requirements can override other grant requirements

This text specifically focuses on audits of US government funded programs. So, let’s start with some basics about how money flows down from the U.S. Federal Government.

The way the money flows

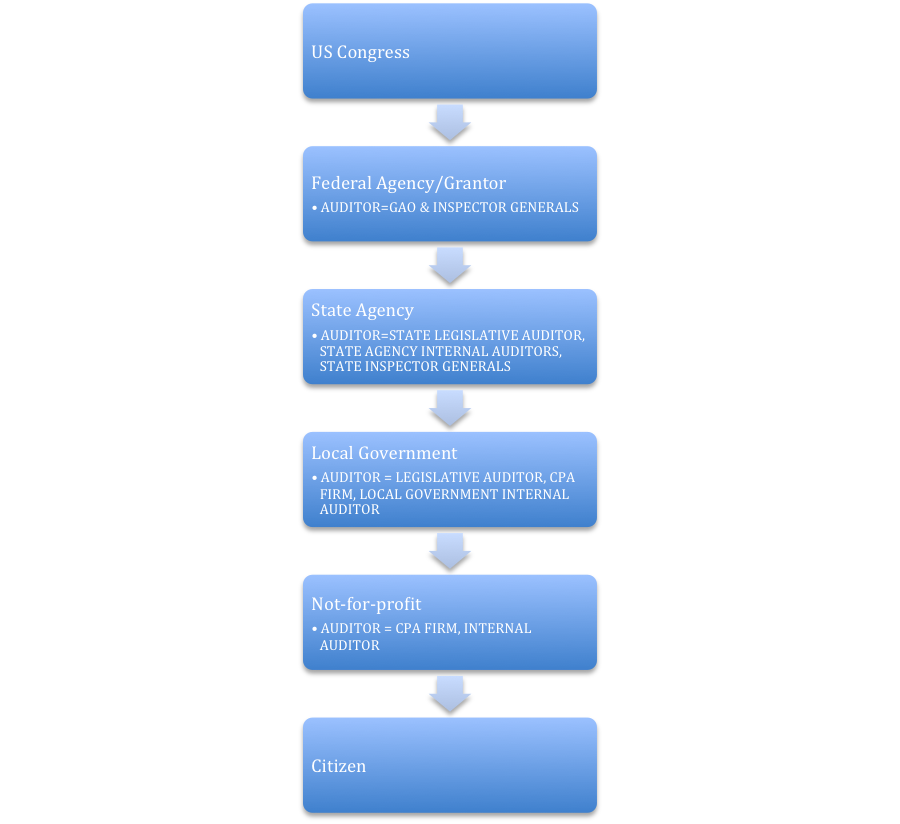

How does the grant funding get from the federal government to the citizen who needs it? The process often involves several entities.

Here is a simple picture of one way that funds can flow from the federal government down to the beneficiary.

For instance, let’s say that a group of educators and experts in homelessness approach Congress and convince Congress that homeless high school students drop out at a higher rate than other students. Congress agrees to fund a program to tutor homeless students. (Yes, there is a program for that!)

Since Congress is not in touch with students directly, it allocates money to the US Department of Education for the homeless tutoring program.

The US Department of Education is not in touch with individual students either, so it sends the money to the states. In our case, it sends the funds to the Texas Education Agency in Austin.

The Texas Education Agency then passes the money through to the local school districts – let’s say the Dallas School District.

The Dallas School District recognizes that it does not have the expertise necessary to make this program a success, so it passes money through to a local not‑for-profit called Homeless Services, Inc., which specializes in working with the homeless community.

Homeless Services, Inc. then pays tutors to work with the homeless high school students.

This is not the way all grants work! Sometimes the federal grantor skips the state and the local school district and passes the money directly to a not-for-profit. Sometimes the funding is consumed by the state and does not pass through to other entities. It all depends on the intent of the program.

How do auditors fit in?

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) audits federal agencies and programs and reports back to Congress. They are the legislative auditor for the federal government. The Yellow Book (Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards) and the Green Book (Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government)– are both authored by the GAO and are very important to the conduct of the audits of federal grant funds.

Each federal agency also has an ‘inspector general’ function. The federal inspectors general are responsible for monitoring or auditing grantees. Federal inspectors general also audit theiragency’s grant activities. The federal inspector general often uses the results of the Single Audit to monitor the grants awarded by the agency.

The term ‘Single Audit’ refers to an audit of grant funds conducted in accordance with the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles and Audit Guidelines for Federal Awards (also known as the Uniform Guidance). You may have heard of OMB Circular A-133 Audits of State, Local Governments, and Non-Profit Organizations. OMB Circular A-133 was replaced by the Uniform Guidance in 2014.

Each state has a legislative auditor who reports results back to the state legislature. Each state has defined the role of their legislative auditor differently. Some legislative auditors conduct the Single Audit at each state agency. I did this work when I audited for the Texas State Auditor. Some legislative auditors audit local governments. Some don’t do either! If the legislative auditor of a state does not perform the Single Audit, a CPA firm (or firms) will perform the audit.

Each state agency usually has its own internal audit shop. The internal auditor is not independent of the subject matter of the Single Audit and, therefore, cannot conduct the Single Audit. State agencies may also create an inspector general who audits the agency internally and audits sub-grantees. For instance, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission’s Inspector General audits Medicaid recipients – like hospitals and clinics – around the state.

Each local government may have a legislative auditor (a city auditor who reports back to the city council) and an internal auditor. The Single Audit of a local government is often conducted by a CPA firm.

Not-for-profits can also have internal auditors, but their Single Audit is usually conducted by a CPA firm.

More about the term “Single Audit”

The Institute of Internal Auditors has been using a new term lately, which I find amusing: “assurance fatigue.” Assurance fatigue describes the exhaustion auditees experience when audited multiple times in a short period of time.

Recipients of federal grants (like the school district and the not-for-profit) complained to lawmakers that they were getting audited multiple times and experiencing severe assurance fatigue. A not-for-profit could get audited by the federal grantor, the state, the school district, their internal auditor, and an external CPA! All the entities involved in the flow of funds wanted to ensure the funds were being spent properly.

Congress responded to this complaint with the ‘Single Audit Act.’ The Single Audit Act designed an audit that should satisfy most of the entities involved in the flow of funds and make it unnecessary for these entities to visit and conduct an audit themselves. Instead of multiple audits, the grantee could undergo one ‘Single Audit’ that would make everyone happy.

Boots on the ground

I am sure the federal grantor would prefer that they had enough auditors on staff to send out into the world to conduct the special, comprehensive audits of federal grants we now call the Single Audit – to be the boots on the ground as it were. But, they don’t have an army of auditors to pull this off, so they subcontract with other auditors down the chain of funding to get the audit done on their behalf.

I find it helpful to think of the Single Audit requirements as terms of a contract between the federal grantor and the grantee’s auditor. The federal government is ultimately paying for an audit that they designed to suit their purposes. The cost of the Single Audit is a legitimate cost that the grantee charges the federal grantor. In essence, the federal government subcontracts the audit work out to other auditors who are closer to the action.

The federal grantors use the results of these localized, subcontracted audits to monitor how things are going out there in the field. If the federal inspectors general find that a grantee or a pass-through entity is misbehaving, they will send their own auditors into the field to investigate. In this way, the federal inspectors general can have fewer employees on the payroll and save on travel costs.

But the federal inspectors general aren’t always happy with the subcontractors. Recently, an audit firm in California hired me to teach them how to do Single Audits faster and with less effort. They ended up learning that they weren’t doing enough to satisfy the federal grantors.

The Single Audit is an intense, granular, and involved engagement. It goes beyond a standard financial audit and involves three components. It also involves complex government expectations, and if you have ever filled out an IRS form, you know that the feds don’t do simple.

I have had the pleasure of working with federal inspectors general quite a bit, and they complain about the quality of Single Audits created by CPA firms. If you would like to see their complaints, Google “PCIE Single Audit Sampling Project.” In this report, a consortium of federal inspectors general performed a quality control review of Single Audits and found over half of them to be unreliable.

What causes the dissatisfaction?

Part of the dissatisfaction is due to the complexity of the Single Audit. The Single Audit is a lot to take on, and some CPA firms are still learning how to do them.

But I think much of the dissatisfaction is due to cultural differences between the federal inspector general’s audit approach and the audit approach of CPA firms.

The federal inspectors general with whom I have worked are what I would call diggers. They spend months and months on an audit and drill down and look at some issues in great and sometimes exhausting detail. Their audit reports are lengthy and take a long time to create.

CPA firms tend to be skimmers. They like to look at a variety of risks, but not in much depth. They are interested in getting in and out of an engagement as quickly as possible so that they can move on to the next gig in the interest of profitability.

Are the diggers ever going to be happy with the skimmers? Never. Are the skimmers ever going to want to go into the detail that the diggers do? No way. There is a happy medium in there somewhere, but I only know of a few audit shops that have struck that balance.

So, what happens when the diggers design an audit? It becomes very granular and detailed. VERY.

A veteran state auditor told me a story that sums up the situation. The state auditor was responsible for conducting the Single Audit for the entire state, and the federal cognizant agency overseeing the audit on behalf of all federal grantors felt that the state auditor wasn’t digging in deeply enough. The state auditor had only 200 staff to dedicate to the project for a portion of the year and made some hard choices about where to spend their time. In other words, they didn’t dig everywhere.

The federal cognizant agency came for a visit, bringing six huge binders full of requirements, and stacked them on the table. The feds said, “We expect you to do what we do. We expect you to do this!” And one of the state auditors said, “Are you kidding? We aren’t doing all that!” At the end of the meeting, they were back where they began, with the state doing a risk-based audit and the feds having to reconcile themselves to not having complete and absolute coverage of the grants.

You, as my CPA firm friends in California realized, will have to make a choice. Will I dig as the feds desire or will I skim? Or will I try to live in the middle? Bid accordingly and anticipate feedback from someone – the client or the feds – depending on the choice you make.

Four major differences

Given this relationship among auditors and the federal inspector general’s expectations, and given that the federal government designed the Single Audit as a mechanism to ensure that a variety of stakeholders is satisfied, let’s take a birds-eye view of the four major differences between a Single Audit and a plain-Jane financial audit.

1. The Single Audit is three audits in one

In order to meet the needs of all of the users of the audit report, the Single Audit Act designed an audit that covers three audit subjects:

- A financial statement audit. The auditor expresses an opinion on whether the financial statements are presented in accordance with GAAP. (As part of the financial statements, the auditor must verify the contents of the Supplemental Schedule of Expenditures of Federal Awards (SEFA). The auditor expresses an “in relation to” opinion on this schedule. This means that the auditor says that the SEFA is fairly presented “in relation to” the financial statements.)

- An audit of internal controls over compliance for major programs.

- An audit of compliance for major programs. The auditor expresses an opinion on compliance.

Here is an excerpt from Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards describing what auditors are required to do on a Single Audit:

§200.514Scope of audit.

(a) General. The audit must be conducted in accordance with GAGAS. The audit must cover the entire operations of the auditee, or, at the option of the auditee, such audit must include a series of audits that cover departments, agencies, and other organizational units that expended or otherwise administered Federal awards during such audit period, provided that each such audit must encompass the financial statements and schedule of expenditures of Federal awards for each such department, agency, and other organizational unit, which must be considered to be a non-Federal entity. The financial statements and schedule of expenditures of Federal awards must be for the same audit period.(b) Financial statements. The auditor must determine whether the financial statements of the auditee are presented fairly in all material respects in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles. The auditor must also determine whether the schedule of expenditures of Federal awards is stated fairly in all material respects in relation to the auditee’s financial statements as a whole.(c) Internal control.

(1) The compliance supplement provides guidance on internal controls over Federal programs based upon the guidance in Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government issued by the Comptroller General of the United States and the Internal Control—Integrated Framework, issued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO).

(2) In addition to the requirements of GAGAS, the auditor must perform procedures to obtain an understanding of internal control over Federal programs sufficient to plan the audit to support a low assessed level of control risk of noncompliance for major programs.

(3) Except as provided in paragraph (c)(4) of this section, the auditor must:

(i) Plan the testing of internal control over compliance for major programs to support a low assessed level of control risk for the assertions relevant to the compliance requirements for each major program; and

(ii) Perform testing of internal control as planned in paragraph (c)(3)(i) of this section.

(4) When internal control over some or all of the compliance requirements for a major program are likely to be ineffective in preventing or detecting noncompliance, the planning and performing of testing described in paragraph (c)(3) of this section are not required for those compliance requirements. However, the auditor must report a significant deficiency or material weakness in accordance with § 200.516 Audit findings, assess the related control risk at the maximum, and consider whether additional compliance tests are required because of ineffective internal control.

(d) Compliance.

(1) In addition to the requirements of GAGAS, the auditor must determine whether the auditee has complied with Federal statutes, regulations, and the terms and conditions of Federal awards that may have a direct and material effect on each of its major programs.

(2) The principal compliance requirements applicable to most Federal programs and the compliance requirements of the largest Federal programs are included in the compliance supplement.

(3) For the compliance requirements related to Federal programs contained in the compliance supplement, an audit of these compliance requirements will meet the requirements of this Part. Where there have been changes to the compliance requirements and the changes are not reflected in the compliance supplement, the auditor must determine the current compliance requirements and modify the audit procedures accordingly. For those Federal programs not covered in the compliance supplement, the auditor should follow the compliance supplement’s guidance for programs not included in the supplement.

(4) The compliance testing must include tests of transactions and such other auditing procedures necessary to provide the auditor sufficient appropriate audit evidence to support an opinion on compliance.

(e) Audit follow-up. The auditor must follow-up on prior audit findings, perform procedures to assess the reasonableness of the summary schedule of prior audit findings prepared by the auditee in accordance with § 200.511 Audit findings follow-up paragraph (b), and report, as a current year audit finding, when the auditor concludes that the summary schedule of prior audit findings materially misrepresents the status of any prior audit finding. The auditor must perform audit follow-up procedures regardless of whether a prior audit finding relates to a major program in the current year.

(f) Data Collection Form. As required in § 200.512 Report submission paragraph (b)(3), the auditor must complete and sign specified sections of the data collection form.

Notice the terms ‘major program’ and ‘compliance supplement.’ I’ll discuss those in more detail in a bit.

- The financial statements of the grantee

- Internal controls over compliance

- Compliance with grant terms and conditions

Most auditors with a few plain-Jane financial audits under their belts feel comfortable auditing the financial statements. But the intensity of the Single Audit requirements regarding internal controls might be a bit of a shock, and the compliance piece can be a little tricky because of the litany of compliance requirements. We are going to focus on objectives 2 & 3 in this text as a more generic course on auditing will cover objective 1.

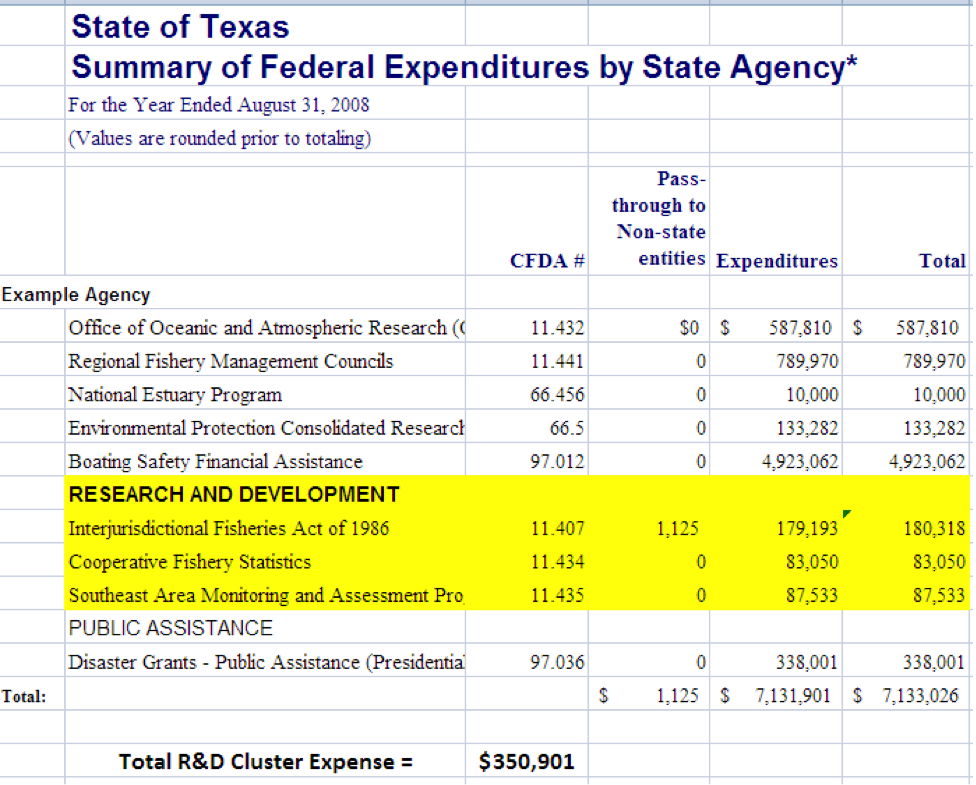

More on the SEFA

The SEFA simply lists which grants the entity received, their identifying numbers, and amounts expended. Here is an example of the format:

I wish I could give you a tip that would allow you to treat all of these pieces (financial statements, SEFA, and compliance) as one audit objective so that your work would be more efficient. But the truth is that the systems and controls over each are different and have to be treated as such. The controls over financial reporting are not the same as controls over compliance. Often an entity will have programmatic managers and finance managers. In larger organizations, these folks don’t mingle much and often do not have the same sensibilities regarding controls.

2. Three layers of standards and requirements

On December 26, 2013, the federal government consolidated the Single Audit guidance, as well as the administrative guidance and cost principles for federal grants, into one document: Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards (known commonly as the Uniform Guidance). It includes the audit guidance originally included in theSingle Audit Act of 1984. The Uniform Guidanceasks that all grantees expending more than $750,000 per year undergo the Single Audit.

InSubpart F– Audit requirements of Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards, one simple sentence, “The audit shall be conducted in accordance with GAGAS,” is worthy of attention.

GAGAS refers to theYellow Book, also known asGovernment Auditing Standards and Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards. The aforementioned Government Accountability Office is the author of theYellow Book.

The Yellow Book auditing standards contain several requirements that cause auditors heartburn – including an intense continuing professional education requirement, stringent independence standards, and the use of the elements of a finding. Every five years or so, theYellow Bookundergoes revision. The next revision is due in 2017.

But that isn’t the only audit standard you need to apply. Inside the Yellow Book, the GAO directs auditors to follow the AICPA’s Clarified Auditing Standards when conducting a financial audit, and then the GAO goes on to classify the Single Audit as a financial audit.

So, with one simple sentence,Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards requires the use of two more auditing standards – the Yellow Book and the AICPA’s Clarified Auditing Standards.

This three-layered set of standards (Single Audit requirements, Yellow Book, and AICPA standards) really wasn’t that big a deal 30 years ago when the Single Audit Act was passed because the AICPA and the GAO were pretty quiet and the standards were pretty stable. Since the Enron debacle, the AICPA and the GAO have been very busy improving the standards. The AICPA standards were significantly revised in 2009 and they Yellow Book has been revised 4 times since 2001. And that means that auditors must stay on their toes and up-to-date with all of the standards in order to perform a high-quality Single Audit.

3. Levels of materiality

The compliance portion of a Single Audit is very granular, and auditors must evaluate risk and materiality at three levels. First, the auditor must determine which programs are ‘major.’ Once the auditor decides which programs are major and thus deserve attention, the auditor must decide which compliance requirements are applicable to that program. And lastly, the auditor must decide whether the applicable compliance requirement is significant or material.

For instance, my local school district receives over 30 federal grants. I know the auditor is relieved that they have to audit only a handful of these grants. And for each of the handful of grants they must audit (which are deemed ‘major’ grants), they audit only applicable and significant compliance requirements –not all compliance requirements.

After working through all these layers of materiality, the auditor opines on whether the entity has complied with every direct and material (applicable and significant) compliance requirement for each major program.

4. A litany of criteria and defining documents

An audit is defined as the evaluation of an audit subject against given criteria – and the federal government gives and gives and gives. The OMB’s Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards is over 100 pages long!

Here is a generic list of the sources of the audit criteria on a Single Audit:

1.Cross-cutting administrative rules – give grantees generic rules on how to manage a federal grant, including status-reporting requirements and closing down a program. These rules are often referred to as “The Common Rule.”

2.Cross-cutting cost principles – tell grantees what they can and can’t spend their money on. For instance, martinis are not allowed, but payroll usually is.

3.Program regulations – apply to the specific program. Is it a grant to help homeless children or build a highway? Specific regulations apply.

4.Grant terms and conditions – inside the grant contract itself, the grantor may list specific compliance requirements.

The grant terms and conditions (#4) can override any of the other criteria. The grant terms and conditions may allow the grantee to do something that is not allowed in the program regulations, and the program regulations may specifically allow something that the cost principles and administrative rules prohibit. It is a bit of a hierarchy.

What does the audit report look like?

In order to understand what we are committed to as auditors, I like to look at the end result – the audit reports. What statements do we put our name behind? On the Single Audit, auditors include three main letters in their audit package:

- An opinion on whether the financial statements were presented in accordance with GAAP. This letter also includes an ‘in relation to’ opinion on the SEFA.

- An opinion on compliance for each major program. Usually all of the opinions are listed inside one letter.

- An internal control letter. You do NOT express an opinion on internal control.

Here is an example of the compliance and internal control letter from the AICPA website as of February 2017. Check back on the Government Audit Quality Center website for the example letters before you publish your letter in case the language has been updated.

Report on Compliance for Each Major Federal Program; Report on Internal Control Over Compliance; and Report on Schedule of Expenditures of Federal Awards Required by the Uniform Guidance (Unmodified Opinion on Compliance for Each Major Federal Program; No Material Weaknesses or Significant Deficiencies in Internal Control Over Compliance Identified

Independent Auditor’s Report

[Appropriate Addressee]

Report on Compliance for Each Major Federal Program

Supplement that could have a Example Entity’s major federal programs for the year ended June 30, 20X1. Example Entity’s major federal programs are identified in the summary of auditor’s results section of the accompanying schedule of findings and questioned costs.

Management’s Responsibility

Management is responsible for compliance with federal statutes, regulations, and the terms and conditions of its federal awards applicable to its federal programs.

Auditor’s Responsibility

Our responsibility is to express an opinion on compliance for each of Example Entity’s major federal programs based on our audit of the types of compliance requirements referred to above. We conducted our audit of compliance in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America; the standards applicable to financial audits contained in Government Auditing Standards, issued by the Comptroller General of the United States; and the audit requirements of Title 2 U.S. Code of Federal Regulations Part 200, Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards (Uniform Guidance). Those standards and the Uniform Guidance require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether noncompliance with the types of compliance requirements referred to above that could have a direct and material effect on a major federal program occurred. An audit includes examining, on a test basis, evidence about Example Entity’s compliance with those requirements and performing such other procedures as we considered necessary in the circumstances.

We believe that our audit provides a reasonable basis for our opinion on compliance for each major federal program. However, our audit does not provide a legal determination of Example Entity’s compliance.

Opinion on Each Major Federal Program

In our opinion, Example Entity complied, in all material respects, with the types of compliance requirements referred to above that could have a direct and material effect on each of its major federal programs for the year ended June 30, 20X1.

Other Matters

The results of our auditing procedures disclosed instances of noncompliance, which are required to be reported in accordance with the Uniform Guidance and which are described in the accompanying schedule of findings and questioned costs as items [list the reference numbers of the related findings, for example, 20X1-001 and federal program is not modified with respect to these matters.

Example Entity’s response to the noncompliance findings identified in our audit are described in the accompanying [insert name of document containing management’s response to the auditor’s findings; for example, schedule of findings and questioned costs and/or corrective action plan]. Example Entity’s response was not subjected to the auditing procedures applied in the audit of compliance and, accordingly, we express no opinion on the response.

Report on Internal Control Over Compliance

Management of Example Entity is responsible for establishing and maintaining effective internal control over compliance with the types of compliance requirements referred to above. In planning and performing our audit of compliance, we considered Example Entity’s internal control over compliance with the types of requirements that could have a direct and material effect on each major federal program to determine the auditing procedures that are appropriate in the circumstances for the purpose of expressing an opinion on compliance for each major federal program and to test and report on internal control over compliance in accordance with the Uniform Guidance, but not for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of internal control over compliance. Accordingly, we do not express an opinion on the effectiveness of Example Entity’s internal control over compliance.

A deficiency in internal control over compliance exists when the design or operation of a control over compliance does not allow management or employees, in the normal course of performing their assigned functions, to prevent, or detect and correct, noncompliance with a type of compliance requirement of a federal program on a timely basis. A material weakness in internal control over compliance is a deficiency, or combination of deficiencies, in internal control over compliance, such that there is a reasonable possibility that material noncompliance with a type of compliance requirement of a federal program will not be prevented, or detected and corrected, on a timely basis. A significant deficiency in internal control over compliance is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control over compliance with a type of compliance requirement of a federal program that is less severe than a material weakness in internal control over compliance, yet important enough to merit attention by those charged with governance.

Our consideration of internal control over compliance was for the limited purpose described in the first paragraph of this section and was not designed to identify all deficiencies in internal control over compliance that might be material weaknesses or significant deficiencies. We did not identify any deficiencies in internal control over compliance that we consider to be material weaknesses. However, material weaknesses may exist that have not been identified.

The purpose of this report on internal control over compliance is solely to describe the scope of our testing of internal control over compliance and the results of that testing based on the requirements of the Uniform Guidance. Accordingly, this report is not suitable for any other purpose.

Report on Schedule of Expenditures of Federal Awards Required by the Uniform Guidance

We have audited the financial statements of Example Entity as of and for the year ended June 30, 20X1, and have issued our report thereon dated August 15, 20X1, which contained an unmodified opinion on those financial statements. Our audit was conducted for the purpose of forming an opinion on the financial statements as a whole. The accompanying schedule of expenditures of federal awards is presented for purposes of additional analysis as required by the Uniform Guidance and is not a required part of the financial statements. Such information is the responsibility of management and was derived from and relates directly to the underlying accounting and other records used to prepare the financial statements. The information has been subjected to the auditing procedures applied in the audit of the financial statements and certain additional procedures, including comparing and reconciling such information directly to the underlying accounting and other records used to prepare the financial statements or to the financial statements themselves, and other additional procedures in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. In our opinion, the schedule of expenditures of federal awards is fairly stated in all material respects in relation to the financial statements as a whole.

The Data Collection Form

The client and the auditor also have to fill out a Data Collection Form to submit to the Single Audit Clearinghouse. The Data Collection Form asks the client and the auditor to share:

- contact information

- audit opinion results

- finding type – compliance, control, fraud

- federal granting agency/department

- compliance item category – eligibility, allowability, Davis-Bacon, etc.

The federal inspectors general extract and analyze information from the Single Audit Clearinghouse in order to monitor grantees.

Each federal inspector general is required to produce semiannual reports that describe their activities and summarize the results of their monitoring activities of grantees. I recommend that you read, or at least scan, these reports for the grantors of your major programs to determine the common compliance issues that are earning the inspector general’s attention. You can also find out what currently concerns the inspector general so you can anticipate questions from them about your auditee/grantee. The reports are easy to find by Googling “Name of Federal Grantor Semiannual Inspector General Report.”

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website:

Yellowbook-CPE.com is registered with the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) as a sponsor of continuing professional education on the National Registry of CPE Sponsors. State boards of accountancy have final authority on the acceptance of individual courses for CPE credit. Complaints regarding registered sponsors may be submitted to the National Registry of CPE Sponsors through its website: